Adam Ondra

hung with sensors.

What makes him

the world’s best climber?

Strong fingers, a perfect technique, a long neck? Climbing experts have been trying to find out what enables the Czech climber to be at an advantage. iRozhlas’s data journalists have measured his movements using motion capture technology. They have found a feature that surprises Adam himself.

Twenty-five-year old Adam Ondra is the world’s best climber both on the climbing wall and on rocks. Last week he added a title of vice-champion to his two championships in lead climbing (video). Last year he climbed the most difficult route in the world, Silence, in Flatanger, Norway (video).

Many experts have been analysing Adam’s performances, looking for the ingredients that enable him to be ahead of others. Most recently, they have been scrutinising his climbing of Silence. The most detailed – and by far the most interesting – is American trainer Erik Hörst’s analysis. He describes the energy saved in the difficult sections, praises Adam’s ability to take a rest and is excited by his working with breath, which is assisted by regular shouts on the rock, although their meanings can be best understood by the Czechs.

However, the existing analyses are only focused on some features of Adam’s style and often indirectly. Most experts’ opinions can only be based on videos or performance tables. There is still a lot to discover. Moreover, in the Czech Republic Adam is readily available for tests and discussions of his results. After all, looking for what makes his style so outstanding is interesting for him as well since he climbs intuitively and an analytical view surprises him from time to time.

“I am weak in comparison with others”

A climber’s movement is extremely complicated. Unlike endurance running, where we measured a runner’s load by pulse, muscle oxygenation and blood flow sensors last year, climbing has no “right” indicators that could describe it in its entirety. There are a lot of options: the most traditional one is measuring the strength of the fingers, hands and arms; we can also analyse the speed, smoothness and accuracy of the movement on the climbing wall as such, watch how performance is affected by the climber’s psyche (e.g. the fear of falling down); or we can go to the very core and try genetic testing as suggested by analyst Erik Hörst.

Therefore, we arranged a meeting with Adam before the initial design of the measuring.

The almost 190 centimetres tall Adam Ondra is an oddity in his sport: most sport climbers are shorter and quite thin except for their well-defined muscles. What also stands out is Adam’s long neck.

“There’s definitely no point in testing strength,” says Adam. “That won’t show much as I’m not exceptionally strong. I am weaker than others but I can climb more.”

Weaker means that hanging on a two-centimetre edge he can hold 1.1 times his bodyweight on the fingers of one hand. Climber Alex Megos, who Adam regards as his closest rival, can hold 1.3 times his own bodyweight. Adam’s performance was estimated and Alex’s measured by Lattice, an analyst server.

Along with his manager, Pavel Blažek, who plays the role of the strict guy because otherwise Adam would agree to everything and have no time left for training, they explain what he excels in.

“My hips are fairly mobile, so I can cling better to the rock,” Adam continues. “Having my centre of gravity closer to the rock means that I can use my legs thoroughly and I don’t need to hold on to the holds so strongly. So, I save my power.”

Both of them mention Adam’s intuitive climbing.

“I’ve been climbing basically since I was born and until I was twelve I hadn’t known there was any other world outside the rocks,” says Adam. “Lots of decisions are made by my intuition on the rock. It all seems automatic and obvious to me. Sometimes I almost feel as if I were a toy, a Lego, and the movements of my hands and legs were being made by someone else and I were just watching it from a distance without being able to influence it. It’s fantastic to be on the rock in this kind of weightlessness,” he enthuses.

That is connected with the last unique feature that Adam and Pavel mention. Thanks to his intuition and excellent muscle memory he can remember all the steps in no time and when he is climbing, he isn’t hampered by thinking about it, he just climbs automatically. As a result, he can climb the same route faster than other climbers.

“It’s easy: I’m either climbing or relaxing,” says Adam. It sounds trivial. However, in a broadcast from the World Championship a co-commentator, himself a climber, notes admiringly how this advice has helped him.

What Adam means by this rule is illustrated by the aforementioned video of his Silence climb, or more precisely, by four minutes of the climb that can’t be seen in the video. After the first difficult section Adam hangs on the rock using only one leg wedged into the rock shaking his arms calmly for a long time. During the first tests he could stay in the same place for 15 seconds. For better “relaxation” on the route he had spent weeks working his calf muscles.

Gollums on a climbing wall: film-makers’ sensors measuring climbers

Adam wasn’t interesting in measuring his brute force, while genetic testing was not within our compass and was, above all, beyond our capabilities of interpretation.

However, what we did consider measureable as well as visually interesting was his joint mobility and the technique that enables him to outperform climbers who are officially stronger. All we needed was find a collaborator that could record the climber, hung with sensors, on a rock and transfer the movement of his joints into a 3D model, i.e. the motion capture technology. The same process was used to create the film character Gollum (video) or Smaug, the dragon, which was set in motion by British actor Benedict Cumberbatch (video).

However, in comparison with the creators of the Tolkien characters our task was more difficult: we needed to aim the cameras on a 20-metre climbing route and shoot it from similar distances. It took us quite long to find the technology that could do it. Eventually, we found it at Masaryk University’s Faculty of Sports Studies in Brno. Besides the measuring as such, their Biomotor Laboratory also helped us interpret the movements although working with a climber was something new for the scholars.

When he is exceptionally in the Czech Republic, Adam Ondra lives in Brno. That’s why it was there that we looked for the challenge that would put him to a test. The most suitable was the hardest route of the HUDY climbing wall in Brno, rated at 8b. In comparison with Adam’s record (Silence is rated at 9c) it is a relatively easy route but for most Czech top climbers it’s the maximum difficulty. The aim of the experiment was to compare Adam’s style with that of another climber, so that route was perfect.

The last thing was to find an opponent, or rather a partner because competition is rare in this sport – climbers on both the domestic and international scene tend to cooperate. The problem was that Adam is the only professional Czech climber; the others only do climbing as a hobby. In the end, Adam chose his “opponent” himself: he approached Štěpán Stráník, a champion of the Czech Republic and vice-champion of the world in bouldering, a more of a strength version of lead climbing. As a boulderer, Štěpán is a strength rather than technical climber, so the difference in their styles could become apparent.

A pulse rate lower than yours in the office

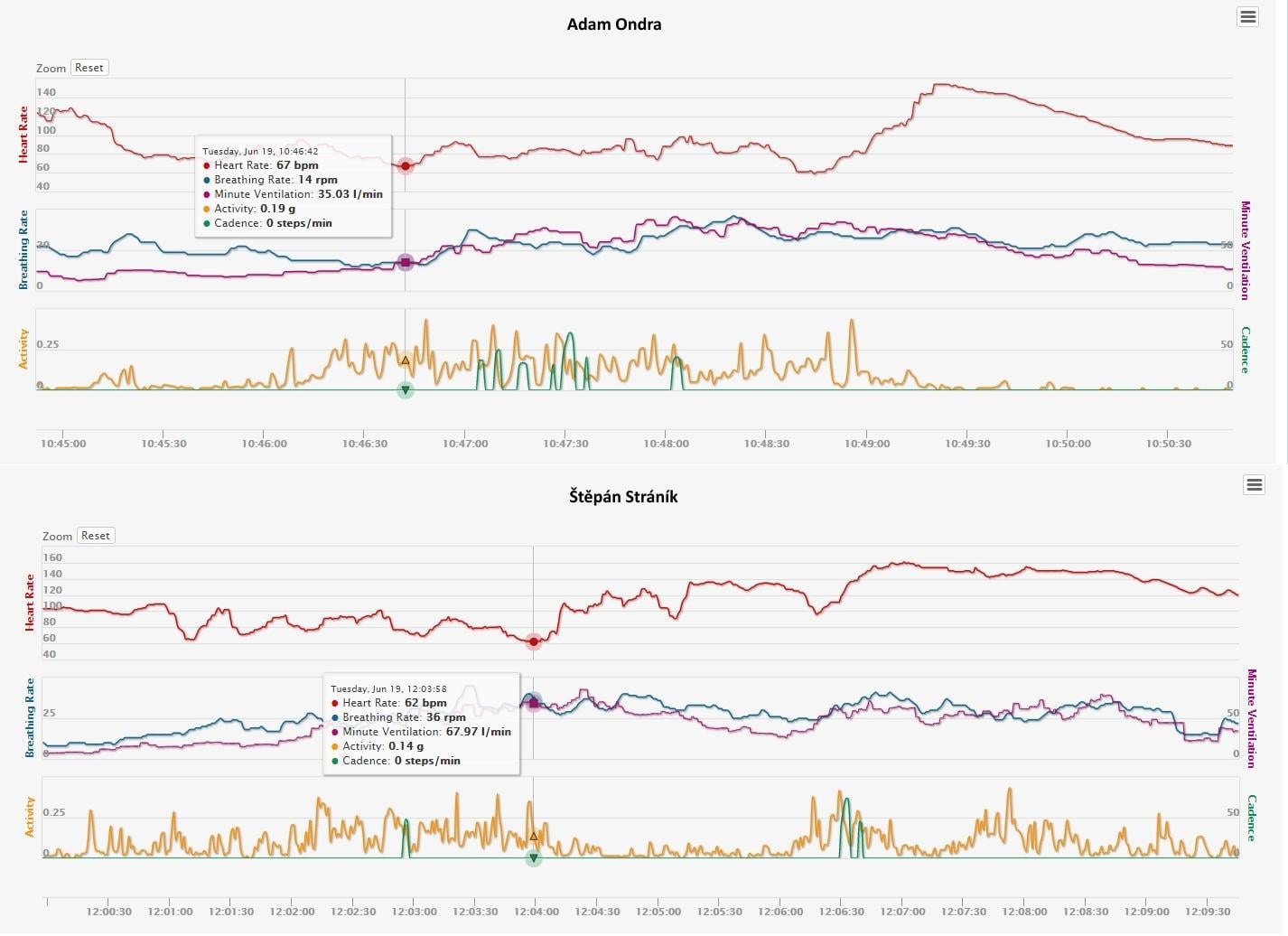

Just before the measuring the climbers put on “smart” T-shirts measuring their pulse and respiration rate so that we could get an idea of their physical and mental load. Position recording sensors were put on their joints. We had to hurry because Adam can’t bear to wear his climbing shoes, which are several sizes smaller, longer than five minutes. Six cameras were aimed at the most difficult point of the route.

During Adam’s first attempt we watched his pulse rate in amazement as it was the indicator that was supposed to show his physical load best. Under the wall it was about 110 beats per minute, which is slightly over the usual rate of an adult man. We had expected his pulse rate to increase to about 150 beats per minute during the performance. However, as soon as Adam swung himself up to make the first move, his pulse rate began to drop, in some places to fewer than 70 beats per minute, which is lower than the rate that most readers of this article have sitting in their offices. His respiration rate showed a similar development.

Adam climbed the twenty-metre route in just under three minutes. Immediately after that his pulse rate increased to 170 beats per minute for a short time.

“Once he finishes climbing, his respiration rate and volume increase spontaneously,” says Jiří Dostal of the Institute of Sports Medicine. “As a result, his body immediately starts regenerating.”

Before we managed to take his T-shirt off, Adam was captured by radio documentarists, who began recording. When he was asked about the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the curve went up to 150 beats per minute. Like other climbers, Adam disapproves of the form of the Olympic tournament, where three disciplines – lead climbing, bouldering and speed climbing – will be combined into one. “Given that the vast majority of elite climbers specialise in one discipline only, the sport’s Olympic Games debut is sure to be a captivating, exciting, and completely unpredictable spectacle,” the International Olympic Committee defends the decision.

“It’s a bit like asking Usain Bolt to run a marathon and then do the hurdles,” British champion Shauna Coxey comments in an article promoting the Tokyo Olympics. While she likes this combination, most other climbers reject it.

Štěpán Stráník’s pulse rate was also low at the beginning – about 100 beats per minute. However, Štěpán spent over five minutes on the wall and had to rest in a few places. At the end of the route his pulse rate as well as respiration rate increased significantly.

The duel on the wall happened faster than we had expected. There was some time left, so, out of curiosity, we quickly measured Adam’s strength.

Surprise in the lab: a head like a pendulum

The finger, arm and shoulder strength tests confirmed our expectations: for example, Adam’s shoulders are 90%– 95% stronger than those of most of the population. The other measured muscles showed similar figures. They were really high although with a three-time world champion you might expect even higher ones.

The measuring also proved that his left shoulder is about a quarter stronger than the right one. “A difference of up to 10% is normal but 26% is a lot because that means that one shoulder must keep trying to catch up with the other,” Tomáš Vodička of the Biomotor Laboratory comments on the results.

“One side of the body is usually stronger in most climbers,” reacts Adam Ondra. “I can do thirteen pull-ups with my left arm, while with the right one it’s only eleven. It’s always been like that.”

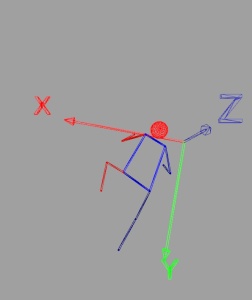

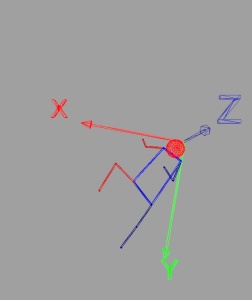

The motion capture model also showed expected results at first. In the middle of a difficult step Adam really clung to the wall, thanks to the high mobility of his hips, with his centre of gravity being closer than 30 centimetres to the wall, while Štěpán’s was 45 centimetres from the wall.

The comparison of the two climbers showed other differences as well: while during a key move Adam’s back is straight and his elbows are at the wall – like in a textbook –, Štěpán arches his back and uses strength to make up for the technical deficiencies.

However, a surprise came after that. When Martin Zvonař, a biomechanics expert and the dean of the Faculty, saw the screen with the skeletons of the two athletes climbing, he noticed a detail we had overlooked.

“Note what Adam does with his head at the end of the move,“ says Zvonař pointing at the screen. “He uses it as a lever: once he has finished a movement he tilts his head back. The centre of the lever is in the centre of gravity and as a result his feet cling better to the wall. I don’t know whether he does that knowingly or intuitively but it definitely helps him.”

“Human’s head weighs seven kilos,” Zvonař continues. “Add Adam’s long neck to it and you get a very effective machine from the point of view of biomechanics.”

He added one more detail: he assumes that Adam’s relatively slim shoulders mean less leverage acting on his fingers, which, as a result, don’t need to exert so much power.

You can compare both climbers’ styles yourselves: by moving up and down the screen or using the drawbar under the video you can go from one shot to another. The left section shows the shots of one of the six cameras, the central section shows a 3D model of the climber’s skeleton, and the graph on the right shows the distance of the climber’s centre of gravity from the wall. If your Internet connection is slow, it might take more time for the individual moves to load.

Adam Ondra

Štěpán Stráník

Ballet and giraffe’s necks

Opening the door of Adam’s family’s house in the Brno quarter of Žabovřesky is Mrs. Ondrová. “I am sorry about the terrible smell, but Adam is just frying some prawns,” she welcomes me. Standing behind her is Adam with his burnt lunch.

“There might be something to it,” he responds when I show him in the video how he uses his head. “I’m 187 centimetres tall but my shoulders are probably at the same height as those of most mortals. My physiotherapist says that my long neck could help me keep my balance.”

“In any case, I have never been taught to use my head so the way I use it must be intuitive,” he adds.

In spite of that, there have been many experts helping him to hone his technique. After he climbed Silence, some experts mentioned the fact that the biggest difference between Adam and other climbers is in the degree of professionalism: in Norway he was accompanied by his trainer, physiotherapist and a few other team members. Physiotherapist Klaus Isele had helped him do a “mock training” session with Adam lying on his back and visualising the whole route (video).

There is a trainer who plays a special role – Jiří Čumpelík, the National Theatre Ballet’s physiotherapist and a “dancer, teacher and yogi” as his business card says. He has never climbed a single route but he might have influenced Adam most, especially by distinguishing between the working leg and the supporting leg, like in ballet, which is something that Adam uses for such a different type of activity as climbing.

“Climbers don’t think about working with the head,” Adam Ondra thinks aloud. “In fact, I don’t know anyone with a physique similar to mine. Although Janja might be similar. She’s got a long neck and a small head.”

He means Janja Garnbret, a nineteen-year-old Slovenian female climber who is regarded as a similar phenomenon as Adam among the males. She excels in two of the climbing disciplines, lead climbing and bouldering. She can also make unbelievable movements using her head to keep her balance (video).

“You can feel free to write about that. I just hope that because of me climbers won’t begin turning their necks into giraffe’s necks, like in Africa,” Adam concludes.

Because he’s the one who enjoys it most

As the sport is becoming more professionalised, the number of studies dealing with climbers’ movements is increasing. There is likely to be a real boom after the sports climbing tournament at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Most analysts concentrate on strength or technique, while others focus on biochemical processes and, like with other sports, we can expect to have the results of genetic testing soon.

Other experts examine climbers’ mental processes, which are particularly interesting in those who climb without using ropes. A Nautilus study subjected top-class free solo climber Alex Honnold to magnetic resonance scanning to test his amygdala, which is the brains “fear centre.” They found out that “his amygdala sleeps in his brain like an old dog in an Irish pub.”

However, the answer might be much simpler.

In summer, on the rocks of Osp, Slovenia, we met a French couple who are professional climbers and keep meeting Adam at camps all over the world. “Why is he the best?” I asked them.

“Because he’s the one who enjoys it most,” they replied without hesitation.

Translation into English by Jan Hokeš